By Sidiki Fofana | Truth in Ink Special Commentary

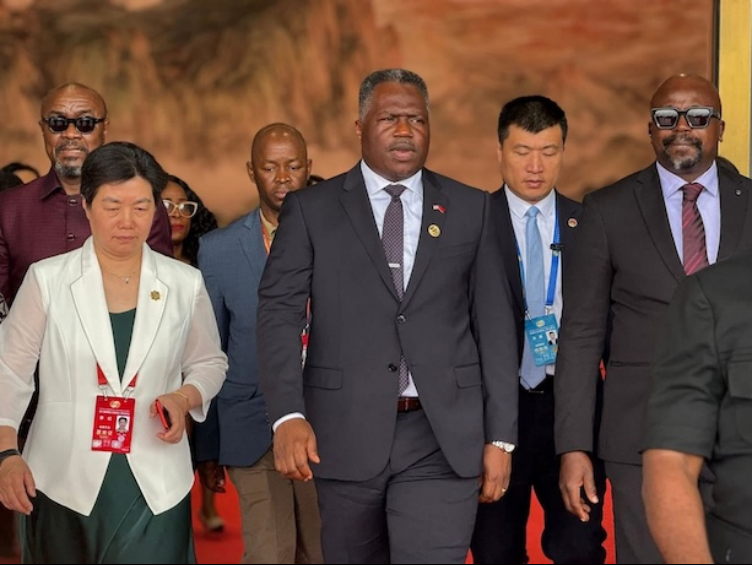

When the late Senator Prince Y. Johnson, the political godfather of Nimba County, anointed Jeremiah Kpan Koung as the new head of the MDR, his ultimate ambition was not just to preserve his local dominance but to see Nimba one day capture the highest office in the land. For Johnson, who had long harbored presidential ambitions, Koung represented the continuity of that dream, a younger vessel through whom Nimba’s long quest for national power could finally be fulfilled.

His calculation was that to reach the presidency, Nimba’s path had to pass through Joseph Nyuma Boakai. Johnson believed the aging statesman was fragile and that if fate or health should intervene, Koung, as his vice president, would constitutionally assume power. “If anything happens to the old man, who will take over? Ehn, that your son,” Johnson asked Nimbians during the Boakai–Koung campaign.

And when the Boakai–Koung ticket narrowly won the presidency, it seemed that the Godfather’s long-held dream was only a heartbeat away from reality. But almost three years later, that dream now trembles under the weight of ambition, betrayal, and division, most of it coming from within Nimba itself. It is a path blocked not by a Boakai’s rerun or a George Manneh Weah as his contender, but by the visible collapse of what was once a united voting bloc joined to a vision of a Nimba national leadership.

What was once a united front of county pride has become a battlefield of personalities. Jeremiah Kpan Koung, who should be consolidating his power as Vice President and preparing a national base, now faces an unexpected war at home. The old Nimba solidarity, Gio, Mano, and Mandingo standing as one, has splintered into rival factions, each claiming ownership of the “Nimba Presidency dream.”

At the center of this unraveling is Senator Samuel G. Kogar, Koung’s most formidable rival and the man who now claims and seeks to position himself as the new heir to the legacy of the late Prince Y. Johnson. Kogar has not hidden his conviction that he, not Koung, is the rightful carrier of Nimba’s political inheritance.

Kogar’s argument is both simple and strategic, Koung, he says, is “not of Nimba paternal origin,” a man elevated by convenience, not conviction, a politician whose claim to the county’s crown is more political than cultural. “If Nimba, must one day produce a president,” Kogar reportedly told his supporters, “It must be through sons who farm in the villages, not boys who simply grew up in county cities as businessmen.”

This quiet but fierce rivalry has fractured the very foundation of Koung’s influence. Senator Kogar now portrays himself as the new field commander of Nimba’s next political phase, drawing his power from the county’s deep connection to sectional ethnicity and naked ambition. He presents himself as the authentic son of the soil, the man closest to the people and truest to Prince Y. Johnson’s original message.

In private discussions across Nimba’s towns and settlements, the conversation is growing.

Koung may be the Vice President of Liberia, but to Kogar and his supporters, Koung no longer commands the county’s heartbeat. The symbolic crown that once sat on Prince Y. Johnson’s head, the title of “Nimba’s Godfather” — is now in contention.

Adding to the turbulence is businessman Musa Hassan Bility, Representative of District 7 in Nimba’s County, who has broken ranks with Koung after accusing him of undermining both his political ambitions, when he sought the speakership, and private enterprises. Bility’s defection, now being slandered by former Ganta City Mayor Dortu Cooper, has shattered the illusion of a united Nimba front.

For Koung, these fractures are more dangerous than any external opposition. The unity that once gave Nimba its political dominance has been replaced by competing ambitions, each man now believing that the presidency, once seen as a collective dream, must wear his own face.

And in that race for ownership, Koung is being cornered in his own house, challenged by Kogar’s rising ambition, weakened by Bility’s defiance, and quietly giving confusion to elders who once saw him as the vessel of Johnson’s prophecy.

For Jeremiah Kpan Koung, the danger is not only losing votes, but also the story. Nimba’s political strength has always been built on unity and identity. Once that foundation breaks, the myth of inevitability collapses.

To become president, Koung must first reclaim Nimba, not by title or appointment, but by trust. He must prove to his people that he still carries the dream of Prince Y. Johnson, a dream that the late Godfather believed would outlive him.

But as Samuel G. Kogar consolidates influence and Musa Hassan Bility fuels discontent, Koung’s once-straight road to the presidency now looks like a narrow path through political fire.

The prophecy that Nimba would one day lead Liberia was built on unity, and unity is what has now escaped it. The house that Prince Y. Johnson built stands divided.

If Jeremiah Kpan Koung cannot win Nimba, he cannot win Liberia. And before he can talk about leading a nation, he must first prove that he can still lead his own county.

For now, the path to the presidency, once envision through loyalty and destiny, appears impossible, not because others have blocked it, but because Nimba itself has.