By Sidiki Fofana | Truth In Ink

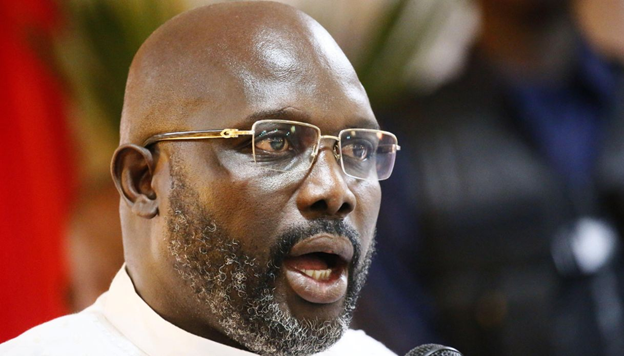

When George Weah finally ascended to the Liberian presidency after more than a decade of trying, he made a remark that deserves more reflection than it often gets. Standing at the Invincible Sports Park, a project now tied to his legacy, he said: “They brought me into politics.”

It was a brief statement, but one heavy with meaning. In that small word “they,” lies the story of the two sides of George Weah, two sides that explain his rise, his contradictions, and the uncertainty of his future.

Oppong: The People’s George Weah

For many Liberians, the “they” refers to the ordinary men and women who saw their own story in George Weah. These are the market women of Red Light, the motorcyclists navigating Monrovia’s chaos, the youth in Clara Town or West Point. To them, he is Oppong or Manneh, the boy from Gibraltar who rose from poverty, crime, and neglect to become the first African to win FIFA’s World Best Player and, eventually, president of his country.

Sociology tells us that nurture and environment shape our destiny, but Weah’s life stands as an argument against that theory. He grew up amid drugs and broken systems yet defied it all. His journey became a parable of possibility” where you begin does not have to dictate where you end.”

It is no surprise then that ordinary people embraced him with such fierce devotion. “He is one of us. He knows suffering. So, when he is president, he will make sure our suffering stops,” a market woman in Clara Town once said.

To these Liberians, Weah is not just a leader. He is proof that their struggle can be redeemed.

“He is our own. He grew up like us. If he can reach there, then our children can too,” a teacher in Logan Town once told me when I was Youth Chairman in 2005

They call him Oppong or Manneh, not Mr. President. Their love is genuine. They do not calculate what they can gain; they don’t demand appointments but transformation of the communities he once lived in; they see in him what they hope for themselves.

Gbehkugbeh: The Political George Weah

But there is another “they.” This side is made up of educated elites, opportunists and desperate politicians who view Weah through a different lens. They call him Dr. Dr. George M. Weah or Gbehkugbeh, a title that translates from his vernacular to “the strong man, the giant, the heavy load.” To them he is the one who carries the “heavy load” to see them ease into position of affluent and influence.

Unlike the market woman, their admiration is not born of shared struggle, but of fear and dependency. They know that in Liberia’s political space, few can match Weah’s power to attract votes. For them, they do not share Weah’s life struggles, but he a ticket to their survival. “You can’t beat him, so better you join him,” one opposition figure admitted off the record. That is the fear. His unmatched electability forces even critics to bend. Fighting him is costly, so they cling to him, not to advance change, but to secure access to power, privilege, and wealth.

Joseph Rudolph Johnson, Liberia’s former Secretary of State, revealed this logic best in 2005 when he left his party to join Weah’s ticket as vice presidential candidate. Asked why, he said: “I was in a small boat on high sea and then saw a bigger boat, what do you expect me to do?

This side of the ” they” thrives on proximity. They flatter him, silence his critics, and attack anyone who gets too close, not out of loyalty, but out of calculation. For them, Weah is not a story of hope; he is a shield for survival. His potential return in 2029 is not about his unfinished legacy, it is about their unfinished desire for aggrandizement.

Two Paths Before Him

Weah himself appears caught between these two sides. When he hinted after the 2023 elections that he might retire, the Oppong side, the people, accepted his decision, though saddened. They believed their hero had already given enough; from the day he wore the Lone Star jersey to the day he delivered his last oration as president.

But the Gbehkugbeh side could not accept it. They need him back. Without his political magnetism, their chance to power collapses. They see his return not as an act of service to the people, but as a guarantee for their own ambitions.

This is the tension that defines George Weah today- a man loved by his people but could be used by his circle. A man pulled between his identity as a symbol of hope and his role as a political vehicle for others’ gain.

Similar Scenarios in Liberia’s History

Weah is not the first Liberian leader caught between love from the people and dependence from elites. Tubman rose as “father of the nation,” but around him grew an elite whose loyalty was measured in patronage, not progress. Samuel Doe, embraced at first as “first indigenous President”, was consumed by opportunists who turned his populist rise into tragedy.

Across Africa, Nkrumah of Ghana was the redeemer whose charisma was drained by sycophants. Yet in Rwanda, Kagame turned legitimacy into discipline, choosing system over loyalists.

And so, the dilemma Weah must confront is will he use his personal popularity to reform a nation or allow it to be exploited for the feeding of opportunists. Confronting this dilemma will determine which sides eventually take to the campaign trail.

The Eve Before Christmas

In Liberia we say: “When the Christmas will be good, you will know from the eve.” The same can be said of Weah’s possible comeback in 2029. His message, the people he surrounds himself with, and the way he frames his second bid will be the clearest window into which side of George Weah will emerge.

Will it be Oppong, the humble boy from Gibraltar whose life embodies the resilience and aspirations of ordinary Liberians? Or will it be Gbehkugbeh, the strong man guarded by opportunists who view him only as a ladder for themselves?

The answer will determine which side we will see not only in the elections in 2029 but if he were to win, which side will govern affecting not only his legacy, but the direction of the country.